Firearms History and the Technology of Gun Violence

This online exhibit was designed to provide context for the 2019-20 Campus Community Book Project topic of gun violence as the UC Davis community reads and discusses Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives, by Gary Younge.

It complements the exhibit, Gun Violence in America, that was on display at Shields Library during October 2019 and a related talk by librarian Matt Conner.

The online exhibit provides a historical perspective on the development of modern firearms, based on the belief that, to understand gun violence, one must understand something about guns.

The First Modern War

The American Civil War (1861-1864), which transformed American history, also changed the history of warfare. It has been called the First Modern War. The reason for this label can be seen in two images from the beginning and end of the war.

The First Battle of Bull Run (July 21, 1861), pictured here, was the first major battle of the war, and it convinced all sides that they were not going to win with a quick victory but were in for a major conflict. With the close-packed formations of men using volleys of rifle fire, the scene would not have been out of place in the Revolutionary War, 70 years earlier. But only a few short years later, at the siege of Petersburg, VA, (June 15, 1864 to April 2, 1865), which led directly to the surrender of Robert E. Lee and the end of the Confederacy, the scene changed completely.

The empty battlefield of modern warfare had emerged, where no one is visible because they have taken cover behind fortifications. This scene resembles the trenches of WWI, 70 years later, in which European armies relearned the lessons of the Civil War at terrible cost. Another feature of the first modern war is the use of all categories of modern weapons, including armored warships, submarines, machine guns and repeating rifles. It even featured aerial warfare in the form of observation balloons. Yet, the radical transformation in tactics did not result from these exotic technologies but from the humble muzzle-loading longarm with one critical difference from the Revolutionary War.

Rifled Bore

The standard rifle of the Union Army of the Civil War was the 1861 Springfield Rifled Musket.

The Confederates used a similar weapon, the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifled Musket imported from Britain. The Springfield rifle differed in two respects, one major and one minor, from Revolutionary War muskets. The minor difference was the percussion ignition system. Revolutionary muskets had used a flintlock system whereby a flint was moved by a trigger mechanism to strike against a metal surface to generate a spark to ignite the gunpowder. The Springfield used a hammer to strike a metal “cap” to generate the spark. The new system was more enclosed and efficient, but fundamentally similar. The major difference was the use of a rifled bore. Whereas musket barrels were smooth tubes, a rifled bore had spiral grooves running the length of the barrel. Anyone who has seen a James Bond movie has seen rifling.

The ’70s themed funky spirals are rifling grooves seen from the viewpoint of a bullet pointed at James Bond. By engraving the soft lead of the bullet in its passage, the rifling imparts spin, which enabled far greater range and accuracy. Where smooth-bore muskets were accurate to less than 100 yards and needed to be fired in volleys to have any effect, the new rifles could hit man-sized targets out to 800 yards. It was this innovation which swept battlefields clean. With such range, it became suicidal to use the massed formations of earlier time, and hiding behind cover was the only option.

Interrelated Advances

The success of the rifled musket laid the groundwork for future advances. For all its achievements, the rifled musket had glaring problems — two in particular. The first was a very complex loading process. The cartridge of the time consisted of a measure of gunpowder and a bullet contained in a paper packet. To load, the soldier tore the packet with his teeth and emptied the gunpowder down the muzzle. He then dropped the bullet after it. Finally, he wadded up the paper and, with the aid of a ramrod, packed everything into place at the other end of the barrel. Then, he reversed the rifle to take his shot. This complicated process was drilled into soldiers as the “Load in Nine Times.” How soldiers achieved this in combat amid whizzing bullets beggars the imagination. The second problem was loading at the muzzle, which required moving between the two ends of a fairly long object. These two problems were answered with three interrelated inventions.

- Enclosed metallic cartridges

- Breech-loading mechanism

- Magazine for multiple cartridges

Metallic Cartridges

Metallic cartridges developed over the remainder of the 19th century into the following form.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en Rather than utilizing paper packets, ammunition was now enclosed in metal containers with the following components.

- Primer

- Gunpowder

- Brass case

- Bullet

The operation is as follows. A firing pin, activated by the trigger mechanism, strikes a disk of shock-sensitive explosive known as the primer, which is embedded in the base of a brass cylinder called the case. The case also contains gunpowder, and its open end is sealed by a bullet, a conical mass of lead jacketed in copper, which is held in place by friction. The spark from the primer ignites the powder, causing an explosion. The resulting pressure releases the bullet from the case and sends it down the barrel. Cartridges are distinguished in power by their caliber, measured in terms of the width of the bullet at the widest point and the length of the case. The length of the case is correlated with its volume which, in turn, is related to how much gunpowder drives the bullet. English units refer only to the bullet width in inches. Metric units refer to both the bullet width and case length in millimeters. A common example is the rifle caliber .308. This number indicates a bullet diameter of .308 inches. Its metric designation is 7.62 x 51mm.

Locking Mechanisms and Magazines

With the cartridge contained in one unit, it was neither desirable nor possible to load it in the muzzle; it was necessary to load it in the breech. Opening the breech, however, posed grave danger. During the millisecond when a bullet travels down a barrel in modern rifles, the temperature reaches 5000 degrees F, the surface temperature of the sun. The ignition is very close to the shooter’s face. So, if one is going to open the breech with its layers of protective steel, one needs a means of reliably locking it up again. Two basic mechanisms emerged: a hand-operated lever and a rotating bolt of the kind commonly used in the stall doors of public bathrooms. The opening and closing of the bolt constituted a cycle that could be repeated. And the repetition, in turn, suggested the rapid, successive firing of cartridges. This development, in turn, led to the last of the three innovations, a magazine for holding multiple cartridges which could be rapidly loaded and fired. Magazines commonly took the form of a box in which cartridges are stacked in one or more columns and pushed upward into the rifle mechanism by a spring underneath them. Another common design was the drum in which cartridges are arranged in concentric layers, also powered by a spring which feeds them out of an exit port.

The Action of a Gun

A gun’s action is its central mechanism, and with the development of the metallic cartridges, locking mechanisms, and ammunition magazines, the modern action was essentially complete. Its heart is the receiver, a metal tube with cutouts or openings to accept the major components of a gun. (We will consider a rifle from which handgun mechanisms can be understood as a modification.) One end of the tube accepts the barrel for directing the bullet. Underneath the receiver is an opening to accept a magazine which feeds cartridges upwards. Directly behind the magazine is a trigger, which actuates the firing sequence. A lever can be attached behind the trigger, which can be moved forward and back to open and close the bolt. Or the bolt can be cycled by attaching a small handle at right angles to the bolt body that the shooter can rotate and push back and forth. The action is enclosed in a forestock to hold the weapon and a buttstock to brace it against the shoulder and align it for shooting. While complex in detail, the mechanism is very simple in principle. This was a design goal to make the weapon easier for soldiers to use under stress. Some have called it a distillation of industrialization wherein an individual takes input (cartridges), performs a simple repetitive motion (pulling the trigger and cycling the bolt), and produces output (the fired bullet). This correlation situates modern warfare as an outgrowth of industrialization.

Iconic Weapons

The developments above are demonstrated in famous historical weapons.

The Model 1873 Winchester Rifle is widely recognized from John Wayne movies of the Old West and spaghetti Westerns. It is known as the “Gun That Won the West” although its status as a badge of individual heroism has been heavily revised in view of scholarship on the Western expansion. Appearing only 10 years after the Civil War, its operating lever, located behind the trigger, demonstrates one type of locking mechanism used for repeating weapons. Rather than being stacked in columns that protruded below the action, the cartridges were lined up nose-to-tail in a tube beneath the barrel, and a spring, located at the muzzle end, fed them into the action. Though designed as a rifle, the weapon utilized a pistol caliber cartridge allowing 10 cartridges to be loaded, about double the amount of contemporary handguns. The reasons for using a pistol caliber with a rifle were to allow the use of one caliber for both pistols and rifles while gaining extra velocity from the longer barrel of the rifle and increased ammunition capacity. Because of these design features and intermediate power, these and other lever actions have been described as the assault rifles of the 19th century. The Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) was the service rifle of the British Empire from the late 19th century to the Korean War.

Pictured is the SMLE No. 1 Mark III used in WWI. The bolt-action illustrates the other type of locking mechanism for repeating rifles. But the rifle was best known for its 10-round magazine placed just forward of the trigger; this was also the first detachable magazine. The culmination of bolt-action design was the Model 1898 Mauser invented in Germany by the brothers Peter and Paul Mauser.

The rifle was the supreme achievement of everything that a bolt-action was supposed to be: efficient, strong, and safe. And it was manufactured to the highest standards at its factory at Oberndorf, Germany. As influential as the rifle design was the cartridge. German designers utilized the definition of kinetic energy, the energy of motion: Energy = (1/2)mv^2. This equation says that velocity makes a greater contribution to energy than mass, especially at higher values. The equation also says that reducing the amount of mass allows it to move at a greater velocity for a given amount of energy. Accordingly, designers reduced the size of bullets and gave them a pointed “spitzer” design for greater aerodynamic efficiency. The result was a cartridge with much greater accuracy and range. It was known as the .323 or 7.92 x 57mm, 8mm Mauser for short. This cartridge, mated with the Mauser design, showed immediate superiority over American forces in the Spanish-American War of 1898 and the British in the Boer War, and other countries eagerly adopted it. The American Springfield 1903 rifle was a virtual copy of the Mauser for which the United States paid a fee to Germany until America entered WWI in 1917. The Springfield’s cartridge, the 30.06 (.30 caliber developed in 1906) also closely copied the 8mm Mauser and remains the most popular hunting cartridge of all time. All modern bolt-action rifles that remain in use (for hunting and sniping) are based on the 1898 Mauser design.

Supreme Gun Designer

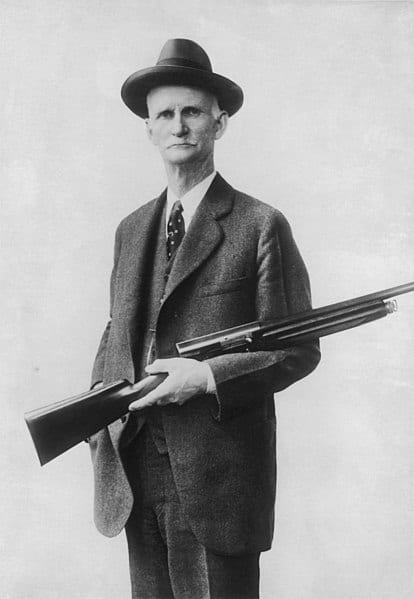

Despite the many people who have designed guns, one individual stands alone among them. John Moses Browning (1855-1926) was a Mormon from Utah and the son of a family of gun designers. He created his first original design at age 13 in his father’s workshop and spent his life at his craft. He died over his work desk in Belgium, over the design of one of his many classics known as the Browning Hi-Power, the precursor to the 9mm handguns that are the military and police standard today.

Shown holding another of his famous creations, the Browning Auto 5 (A-5) semiautomatic shotgun, Browning was the Mozart of gun design. Not only was he at the summit of his craft, but he also demonstrated amazing versatility, designing the best-in-class guns of every type. His creation of semiautomatic and automatic mechanisms helped to shape the 20th century. And his designs and their derivatives provided virtually all the weapons for American soldiers in both World Wars.

The 20th Century and Automatic Weapons

Just as manually operated repeaters increased firepower over the muzzleloaders of the Civil War, designers looked for even greater increases in the rate of fire and lethality of rifles. The record for combat marksmanship was set by Sergeant Alfred Snoxall of the British Army before WWI, who hit a 12-inch diameter plate at a distance of 300 yards, 38 times in one minute with his SMLE. The British army as a whole was proficient in rapid rifle fire as demonstrated at the Battle of Mons (1914), where they overcame German soldiers armed with Mausers, and at the Battle of Gallipoli (1916), where they repulsed large numbers of attacking Turkish troops. Yet, such skill required extensive training. Machine guns, first appearing during the Civil War, addressed this problem by automating the shooting process with a hand crank and multiple, rotating barrels. However, the design could not be scaled down for personal weapons. While the next stage of development took place over a period of time and through several individuals, it can be understood through a single discovery by Browning who, characteristically, produced the best of the new weapons. Browning’s discovery demonstrates the observation of the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, that genius is the ability to use metaphor, that is, to see the relation between two unlike things.

While just about everyone has seen grass blowing in the wind, few have made much of it. Browning saw something different. He imagined the blowing wind as a gaseous medium and the bending grass as a rod, transferring energy from the gas. Why not, he reasoned, have the gases discharged to fire a cartridge directed to move a rod that could work the locking mechanism of a gun? That is, the gun’s own energy could operate itself, saving effort for the shooter and also dramatically speeding up the operation. This insight led to both semiautomatic and automatic weapons that remain as the current state of technology. Semiautomatic guns fire one shot with one pull of the trigger. Automatic guns continue to fire as long as the trigger remains depressed. Browning’s first invention was a gas-operated machine gun known as a “potato digger” for a reciprocating lever in front that suggested a digging motion. It was not particularly successful, but his gas operating principles remain the most successful technology for semiautomatic and automatic weapons today.

Browning’s Masterpiece

Curiously, with all of his rifles, machine guns and shotguns, Browning’s masterpiece is actually considered to be a handgun. Its genesis was the Spanish-American War (1898). Following the mysterious sinking of the battleship U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor, which has never been explained, American soldiers found themselves in the Philippines, fighting against indigenous people who were exchanging one colonizer (the Spanish) for another (Americans). Fighting in heavy jungle at close quarters, American soldiers found their bolt-action rifles to be ineffective and were forced to rely on sidearms.

The American sidearm was a revolver chambered in the .38 Long Colt, and it proved inadequate. Highly motivated attackers would run down a stream of bullets to close with the shooter before expiring. The army turned to Browning for a solution. He decided to resurrect the heavier .45 Long Colt from frontier handguns and mate it with a semiautomatic handgun. His mechanism was called recoil-operation. Rather than utilizing the gases of discharge, the weapon used Newton’s Third Law of motion: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The process can be understood through the photo of his creation below.

The handgun was designed so that part of it was fixed and part allowed to slide along a track. The force of the discharged bullet forward exerts a force backwards on the gun. The lower part remains in place while the slide retracts. As it does so, a small hook (extractor) pulls on the rim of the empty case, dragging it backwards until it strikes a projection (ejector) that throws the case out at just the right speed and angle to exit the ejection port at the top of the slide. Continuing to the rear, the slide cocks the hammer. In the meantime, with the breech clear, the next round is pushed upward from the magazine in the handgrip. The slide now returns forward under spring pressure, stripping off a new round and pushing it into the chamber where it is ready to be fired. Firing one round with each press of the trigger, the pistol’s seven-round magazine could be emptied in a little over one second. Browning’s redesigned cartridge, the .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP), utilized a relatively heavy, slow-moving (speed of sound) bullet. Its impact could stop a running man in his tracks or flip a standing man backwards. Combined with an extremely rapid operation, the pistol proved devastating. However, it arrived too late for the Spanish-American war and entered service in 1911 which has led to its name, “1911”. Apart from minor alterations, this handgun remained the official service pistol until 1985. All modern semiautomatic pistols are based on Browning’s design.

The Devil’s Paintbrush

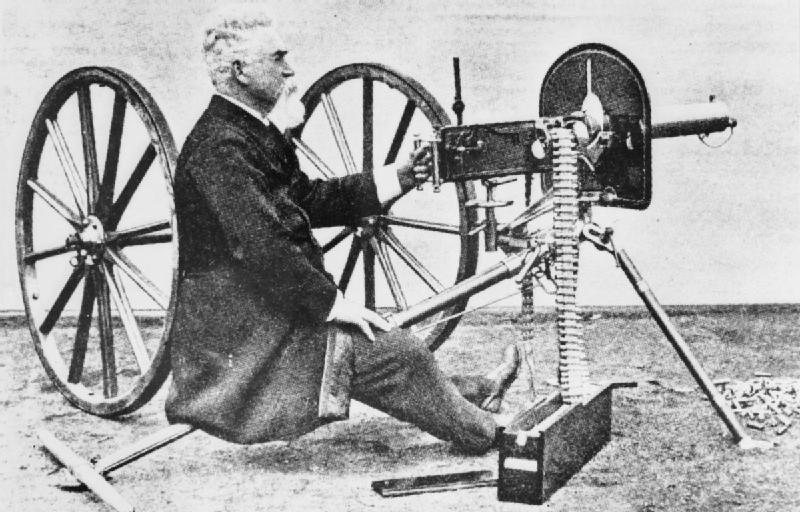

Machine guns were actually invented in 1885 by another influential inventor, Hiram Percy Maxim, an American. He used a somewhat different principle from Browning, recoil operation, similar to Browning’s 1911. Where Browning was an indifferent entrepreneur, who had disagreements with American companies like Winchester and ultimately left the United States to finish his career in Belgium, Maxim was a spectacular success in business. His entire career of firearms development was based on the advice of a friend who reportedly told him, “If you want to make money, find a way for the Europeans to cut each other’s throats faster.” Maxim proceeded to do precisely this, inventing a belt-fed, water-cooled, squad operated machine gun, which could reliably fire 500 rounds per minute.

The suggestively named “Devil’s Paintbrush” produced a large flash at the muzzle, reminiscent of a paintbrush. And unlike rifles, which were designed for shooting point targets, the machine gun covered whole areas with destruction. Dean of gun historians, Ian Hogg, states that, “You could put an idiot behind the Devil’s Paintbrush, and still get your 500 rounds a minute.” The firepower of entire Civil War armies could now be wielded by a single soldier. Maxim’s machine gun was adopted by both sides in WWI and defined the trench warfare of that conflict. As a result, he achieved his dream, receiving honors from the European monarchs whose subjects he helped slaughter by the millions. But his work left him completely deaf by the end of his life.

WW1 Tactics and Weapons

Just as the rifled musket defined the battlefields of the Civil War, Maxim’s machine gun, combined with concentrated artillery fire, defined the battlefields of WWI (1914-1918). The outcome was largely the same. Faced with overwhelming fire, soldiers dug into the ground to protect themselves. The configuration of weapons elevated the defense over the offense, and the war settled into a stalemate for much of its four years. The trenches of the opposing side, separated by No-Man’s-Land, divided Europe from Belgium down to Italy. Each side mounted costly attacks that were repulsed with neither side gaining the upper hand. The futility of the war and its appalling cost were distilled into the fighting in Passchendaele, France. Not only were the soldiers forced to hide in the ground, but the ground itself, due to heavy rains and the relentless churning of bullets and shells, became a morass. One soldier reported to his commander that “it is not possible to consolidate porridge.”

A British general, upon seeing the battlefield for the first time, broke down and exclaimed, “Good God! Did we send men to fight in that?” The fighting is also memorialized in Siegfried Sassoon’s poem “Memorial Tablet” in which the speaker says, “I died in hell/They called it Passchendaele.” Such was the impasse that it was only broken by geopolitical alliances and logistic changes resulting from the entry of the United States. Nevertheless, military minds were actively at work to solve the puzzle of the trenches. And while their inventions did not prove decisive in the war, they heavily influenced future conflicts. The basic problem of trench warfare was two-fold: How do you cross No-Man’s-Land, and how do you overcome the defenders of the trench on the opposite side? We will consider these problems in reverse. Soldiers, who reached the opposing trench, found themselves ill-equipped with their bolt-action rifles, which were unwieldy in close-quarters combat. They were difficult to operate and their capacity was small. In practice, the rifles amounted to little more than clubs. Soldiers resorted to 1911 pistols, which gained a reputation for effectiveness, but they were still sidearms. One solution was created by American general John M. Thompson.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en His submachine gun was a carbine-length weapon that fired the .45 ACP cartridge on full automatic with a high rate of fire — about 800 rounds per minute. The drum, which holds 70 rounds, feeds the voracious appetite of this weapon, and the two pistol grips allow the shooter to retain control during the powerful recoil. The weapon was designed as a “trench broom” with which soldiers could sweep the trench clear of enemies and became the iconic “Tommy gun.” However, the weapon arrived too late to impact the war. With the cessation of hostilities, the army had no interest in the weapon, and Thompson cast about for ways to market it. Hardware stores offered it for sale at the (then expensive) price of $25, but failed to arouse the interest of the general public. But Prohibition gangsters found it highly desirable and used the submachine guns in large quantities. Their use in the Valentine’s Day Massacre (February 14, 1929) led directly to federal restrictions on machine guns as “unusual and dangerous weapons” in the National Firearms Act of 1934. The other problem of trench warfare was crossing No-Man’s-Land in the first place. A preparatory bombardment on the enemy trenches needed to be stopped well in advance to avoid killing their own side. During this lull, both sides raced into position, the attackers to cross to the other side, and the defenders to man their firing positions and set up their machine guns. Since the defenders had shorter to go, they invariably won. Some means was needed to suppress the fire of the defenders while the attackers were in transit. Bolt-action rifles were too slow and difficult to operate on the run while submachine guns were too short-ranged and inaccurate. Once again the army turned to John Browning. He decided to modify a rifle to make it fully automatic. It was equipped with a box magazine which could be emptied with a pull of the trigger in two and a half seconds.

The weapon, known as a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), was designed to be used in a technique known as “marching fire”. Holding the rifle at the hip, the soldier would fire a burst every third step or some regular interval, suppressing the enemy with the long range rifle cartridge as the attackers maintained their advance. Like the Tommy gun, the BAR arrived too late to have a significant impact on the war. However, it went on to a storied history afterwards as one of the first portable, medium machine guns. It was also the favored weapon of Clyde Barrow of the notorious criminal team of Bonnie and Clyde. Barrow obtained a BAR by raiding a National Guard Armory, and much of the team’s success was based on the fact that they were much more heavily armed than the police opposing them. Bonnie, herself, did not fire weapons, but she loaded Barrow’s magazines for him. The pair’s end came at the hands of police armed with the same weapons as them. Police ambushed the pair in a car that was slowed by a roadblock. First, the police emptied automatic rifles, then shotguns, and finally handguns into the car before it came to a stop. After the gangster era, the BAR served as a squad automatic weapon in American armies through the Korean War.

Stormtroopers

The Germans had their own version of technology and tactics to overcome trench warfare, and their efforts were so far-reaching as to have entered popular culture.

The term “stormtroopers” conjures up the vaguely comical, armored soldiers of Star Wars, who get mowed down in large numbers by the heroic rebels. As it turns out, their appearance bears a distinct resemblance to their historical namesake from WWI.

But here similarities come to an end, as the German stormtroopers were highly efficient soldiers who came very close to winning the war before American troops and weapons could arrive in force. The tactics of the stormtroopers can be inferred from their equipment. They were issued extra supplies of hand grenades as well as gas masks. They also carried their own brand of submachine guns as well as flamethrowers, a German invention. The stormtroopers’ tactics have become standard for modern armies and especially for Special Forces and relied on three principles: speed, surprise, and violent execution. These principles also persist in the slogan “Shock and Awe.”

The stormtroopers began their attack with poison gas. While the enemy was busy donning gas masks, the stormtroopers showered them with grenades and sprayed them with submachine guns. When the enemy broke, the stormtroopers did not turn sideways to consolidate a trench line but continued to the interior of the position where they would attack again. Considering an enemy position as an organism, the stormtroopers worked as a fast-moving virus, striking repeatedly and causing a systemic shock far out of proportion to their numbers. Their answer to trench warfare, not unlike the Americans, lay in the combination of mobility and firepower.

While their efforts ultimately failed, the stormtroopers went on to play an important role in the Nazi regime that followed. The shame and resentment felt by the defeated German population after the war was particularly acute for them as elite troops. Thus, they moved naturally into a new role as the brownshirt street thugs of the Sturmabteilung (SA) who helped propel Adolf Hitler to power. The name translates as “Storm Detachment” showing its antecedents in the stormtroopers. However, another irony lay in store for them. While Hitler appreciated the SA’s ability to disrupt the institutions of the Weimar Republic, he knew that ultimate power required the support of the professional German military which the SA hoped to replace. Thus as part of the “Night of the Long Knives” (June 30 to July 2, 1934) in which Hitler assassinated all of his political opponents, he eliminated the leadership of the SA, and the brownshirt rank and file melted back into the population.

But the stormtroopers’ legacy was not done. Hitler appreciated the idea of political soldiers devoted entirely to him, so he retained a cadre of personal bodyguards known as the Schutzstaffel (SS). These were then steadily extended into new organizations such as the secret police. With the outbreak of war, they were formed into combat units (Waffen SS),known for their fanaticism and atrocities, and ultimately became a parallel organization to the regular army. The blitzkrieg method of warfare practiced by the German army also owed much to the stormtroopers. Even the U.S. Marines in the Pacific War made use of the stormtrooper doctrine in their island-hopping strategy, which hit key strongpoints, bypassing enemy units to be surrounded and overcome at leisure.

“The Greatest Battle Implement Ever Devised”

With WWII widely regarded as a continuation of the WWI, the interwar years were a period of preparation. During this time, the United States determined to develop a semiautomatic battle rifle to improve over bolt-action rifles by firing one round with each pull of the trigger. With automatic rifles like the BAR and semiautomatic pistols like the 1911, one might suppose that this would be a simple adaptation. However, in practice, it proved extraordinarily difficult. Solving this problem required the full attention of a mechanical genius for two decades. John Cantius Garand was a Canadian emigre who displayed signs of inventive brilliance from a young age.

He was a crack shot who would astonish people at fairs by hitting every target at shooting galleries for hours. He also displayed eccentricities. Intrigued by ice skating, he maintained a rink in his living room for constant practice, which he only gave up on marrying in middle age. The Springfield Armory, the government arsenal for small arms, hired Garand and made the design of a semiautomatic rifle his only task. During exhaustive experimentation, Garand made a key breakthrough by adopting the long stroke piston of the BAR. This was a rod lying under the barrel which transmitted the gas of discharge backwards to operate the bolt.

As shown, Garand’s design bleeds off gas near the muzzle of the rifle and routes it to apply pressure on the operating rod. Browning’s original vision of grass blowing in the wind reached its full development here. The Rifle, Caliber .30, M1, as the army designated Garand’s creation, was completed in 1936, just in time for WWII. Mass-producing such a complicated and revolutionary design proved to be another challenge. Industrialists granted that the weapon was ingenious but claimed that it could not be produced on a large scale. Garand then showed that his ability was not limited to designing individual weapons but included entire production processes. He single-handedly invented new machinery that enabled production of the rifle for WWII. By the end of its manufacture in 1955, approximately five million of the rifles were made to the highest tolerances.

The rifle proved to be not only accurate, powerful and fast, but extremely reliable despite the precision and exact timing required for semiauto operation. The mechanism worked flawlessly in tropical jungles, deserts, winter snows, and driving downpours, providing American soldiers a significant advantage over their Axis counterparts in every theater of operation. George S. Patton, the famously acerbic American general who commanded armored divisions, described the M1 rifle as “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” The success of the rifle led to a bill in Congress proposing to award Garand with special recognition and a sum of money for his contribution to the war effort. However, lawmakers decided that Garand’s salary at the Springfield Armory was sufficient and voted the bill down.

The Eastern Front: The Cradle of the Assault Rifle

In fact, the M1 Garand was not the most effective rifle of WWII, although because of its large numbers, it may have had the greatest impact on the war. To understand the most lethal rifle of the war, it is necessary to understand the environment and circumstances in which it was created. This environment was the Eastern Front where Germany and the Soviet Union fought each other. This front is obscure to the American historical sense because it was far removed, but it was also the center of gravity of WWII. While it is hard to discriminate among events of mass carnage — and while WWI, “The Great War,” had its uniquely horrifying aspects — there are concrete reasons why the Eastern Front of WWII may have been the greatest land conflict in history. It covered the most land area in thousands of miles of open steppe and forest. It involved the largest numbers of combatants. Nazi Germany lost five million dead against the 300,000 American casualties in all theaters of the war. Russian losses are unknown but have been estimated to be as high as 20 million soldiers and civilians. Both sides were filled with hatred that began as racial and ideological, but, after an exchange of atrocities, took on a life of its own. Typically neither side took prisoners, and desperate and fanatical fighting, such as that on the atolls of the Pacific enveloped an entire continent. Since the fighting was conducted as total warfare in Russian territory, their civilians also suffered terribly. Finally, the weather was abominable in all seasons with heat and dust in the summer and downpours and mud in the fall and spring. But worst was the winters where the temperatures routinely dropped to -40F. These brutal conditions worked to peel back the veneer of civilization even further.

The circumstances of the Eastern Front have prevented widespread information about it. The Germans, on the losing side and with few survivors, were not disposed to write about their experience. Personal memoirs were not encouraged in the Soviet communist system. However, one memoir has emerged from the German side that many consider to be one of the foremost memoirs of this war, or any other. This memoir was written by Guy Sajer and entitled, The Forgotten Soldier . It chronicles the experience of a French teenager who volunteered for the Germany Army, the Wehrmacht, and fought through some of the worst combat on the Eastern Front. As a distillation of his experience, Sajer writes of his first contact with the battlefront. Having endured extreme hardship in winter as a supply soldier, including firsthand experience of death, he still perceived the front lines as something fundamentally different. “I remember seeing what looked like a disintegrating scarecrow flying through the rubble in a cone of flame, and falling in several pieces onto the edge of the trench, before rolling to the bottom… I should perhaps end my account here, because my powers are inadequate for what I have to tell. Those who haven’t lived through the experience may sympathize as they read, the way one sympathizes with the hero of a novel or a play, but they certainly will never understand as one cannot understand the unexplainable. This stammering outpouring may be without interest to the sector of the world to which I now belong. However, I shall try to let my memory speak as clearly as possible… I shall try to reach and translate the deepest level of human aberration, which I never could have imagined, which I never would have thought possible, if I hadn’t known it firsthand.” (68-69) Such was the cauldron that produced the most lethal rifle of the war, the modern assault rifle. Yet, some antecedents of the assault rifle went all the way back to WWI. German military analysts found that the vast majority of fighting fell within a “combat radius” of 400 yards. Thus the materials that went into killing beyond that distance were largely wasted and demanded repurposing. Other factors were the weapons that the Germans faced on the Eastern Front. These included the Ppsh41, the Soviet tommy gun, and the 1891 Mosin-Nagant bolt-action rifle.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

These were standard weapons of the time. However, the Soviets had many more of them with their enormous numerical superiority, and the Germans needed more than parity in response.

Sturmgewehr 44: The First Assault Rifle

In response to the demands of the battlefield, the Germans developed the Sturmgewehr (Stg) 44 whose name translates as “Assault Rifle.” Its model number is derived from the year of its issue, 1944.

As can be seen, the Stg. 44 has several defining features. It was a carbine-length weapon which possesses a switch with three settings: safe (which renders the gun inoperable), semiautomatic, and automatic. The rifle has a large detachable magazine of 30 rounds to feed the automatic setting and a pistol grip, separate from the buttstock, to stabilize the weapon in rapid-fire. As innovative as anything else was the choice of caliber. Evidently, the rifle was a compromise between its antagonists, a submachine gun and a battle rifle, and this extended to the caliber. One would suppose that a middle choice of cartridge meant a middle choice of its two components, the case and bullet. However, the Germans took a different route, selecting the standard Mauser bullet with a shortened case for a new caliber, designated 7.92 X 33 Kurz. In part, the decision was determined by logistics. With its resources strained in the middle of a war, the Germans did not want to start production of a completely new round. But the caliber also neatly served their original design goal. With a shortened case, the new caliber subtracted the extra unnecessary energy of long-range rifle fire while maintaining the weight and striking power of a rifle round. And the smaller package allowed many more rounds to be carried than the standard rifle cartridges.

The new weapon proved extremely effective and by some accounts might have altered the course of the war had it been introduced in time and in sufficient numbers, just as the M1 Garand was supposed to have influenced the war in favor of the American army. For the reason for the weapon’s great success, one might look at its automatic capability, which had such a dramatic effect in the previous war. However, this is certainly not the case for a number of reasons. First, the Eastern Front was awash in automatic weapons of all sizes, shapes and calibers all the way up to automatic cannon, artillery that fired like machine guns. One more comparatively low-powered example would not have made much difference. Furthermore, there were severe limits on the use of the automatic setting. This mode would have consumed a soldier’s entire load of ammunition in a matter of seconds. We also know that the Stg. 44 was not designed to be a machine gun from its relatively slow rate of fire of about 450 rounds per minute. The automatic setting was designed to ensure hits with aimed fire rather than to work as an area suppression weapon. German doctrine called for the rifle to be used on its semiautomatic setting as much as possible.

The reasons for the rifle’s ascendancy can be traced to its interactions with its foes. With its different settings, the Stg. 44 had at least parity. On semiautomatic, it could trade shots with the Mosin-Nagant rifle; up close it could rival the volume of the Ppsh41. But with the flip of a switch, the Stg. 44 could gain an asymmetric advantage. Russian tommy gunners could be picked off before they could get in range, and soldiers charging with their bolt-action rifles could be outgunned by the automatic setting. By putting all these capabilities in a shortened weapon, the Germans gained mobility, which is another aspect of the term “assault.” One does not assault from a stationary position. Soldiers could charge forward less encumbered by the weapon. They could also retreat, either jumping into a truck, or fleeing on foot with less of a burden than a soldier with a full-size rifle. And mounted or on foot, the soldier was better able to conduct lateral maneuvers. It was thus a smart weapon which allowed soldiers to adapt to changing conditions with greatest efficiency, making each line soldier a general in his own right. The weapon also embodied the principles of mobility and firepower introduced so effectively by the stormtroopers of WWI. The assault rifle was a weaponized embodiment of their tactics.

The weapon’s success can be seen readily from subsequent history as virtually all subsequent service rifles are close copies of the design.

AK-47: The Ultimate Assault Rifle

While the Stg. 44 went out of production with the defeat of Nazi Germany, its legacy continued immediately with another weapon that remains in service and is still regarded as the supreme example of the type. The AK-47 (Automat Kalashnikov 1947) Assault Rifle was also born in the Eastern Front. It was designed by Mikhail Kalashnikov for whom it is named. A young tank officer recovering from wounds, he thought about a means to contribute to the struggle for his country and turned to his affinity for invention and design. His initial prototypes found favor with the Soviet military, and he was reassigned to develop them further. His rifle shows a clear indebtedness to the Stg. 44 in its general layout. Its caliber is also a direct copy combining a full-size rifle bullet with a shortened case. It is designated, 7.62X39mm.

However, its interior and operating mechanism were significantly different. Much of it was derived from the M1 Garand that had proven so successful. By moving the Garand’s gas tube from under to over the barrel, one has the basic design of the AK-47. Thus, the weapon culminates the work of three titans of gun design: John Browning with his gas piston, John Garand with his semi-auto adaptation, and Mikhail Kalashnikov. One could hardly imagine a better pedigree for any weapon. But what was Kalashnikov’s contribution if he largely copied Garand’s design? It lay in a radical simplification. While Garand’s design was highly functional, it was extremely complex and required all the resources of American manufacturing at its height. Kalashnikov simplified the design so that it could be built cheaply in the workshops of the Third World and continue functioning in any conditions with a minimum of maintenance. This simplicity and robustness were key to its historical role.

While the AK-47 was never used in the defense of the Soviet Union for which it was designed, it played a crucial role in the Cold War struggle of ideologies. As part of the export of Communism, the AK-47 was sent in vast quantities to support Soviet satellites and to assist revolutions to bring more countries into their sphere. The AK-47 is the only rifle that appears on a national flag, that of Mozambique, in recognition of its role in establishing that country. Over 100 million copies of the weapon have been produced, far more than any other, to ensure its existence into the foreseeable future. Though not especially accurate, the AK-47 remains supreme at the design goals of the original assault rifle to produce acceptable accuracy out to 400 yards in high volume with unfailing reliability.

AR-15: “America’s Rifle”

With America’s success in WWII, it took longer to embrace a concept of the defeated foe. America’s version of the assault rifle did not appear until the beginning stages of the Vietnam War and took a somewhat different route. Rather than a close copy of the German design, the American weapon sought innovation. In many ways, it was a creature of its time, specifically, the Sputnik era when America was obsessed with technological improvement to surpass the Soviet Union. Rather than relying on established gun designers, the AR-15 was created by an aircraft engineer, Eugene Stoner, who sought to apply his expertise to guns. The designation “AR” means Armalite Rifle and refers to the Armalite aircraft corporation that was involved in its creation.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Even decades later, the original design has the futuristic look of a space gun.

Stoner’s greatest innovation lay in the choice of caliber. In the quest for medium caliber ammunition, he reversed the decision of Russian and German designers. Rather than using a large bullet and a small case, Stoner opted for a large case and a small bullet. His caliber came to be called .223 or 5.56X45mm. The bullet diameter was comparable to a .22 rimfire, a recreational weapon for children, but Stoner harnessed it to the equation of Kinetic energy, E = (1/2)mv^2. A bullet of small mass enabled an increased velocity that was vastly enhanced with the extra powder of a larger case to achieve extreme levels. Essentially, he extended the logic of the Mauser brothers in using smaller, faster bullets. Where conventional rifle bullets travel at 2400 feet per second (fps) or about 2000 mph, the 5.56 bullets travel at over 3000 fps or about 3000 mph. While this resulted in somewhat improved accuracy with a flatter trajectory, the bullet design was largely motivated by more damaging wound ballistics as discussed in the next section.

Stoner’s other innovations were to extend the principles of the earlier assault rifles by using synthetic materials, especially plastic, to make it lighter and cheaper to build. He also removed Garand’s piston, choosing to let the discharge gases push directly against the bolt. This design feature known as Direct Gas Impingement (DGI) remains controversial and has not been reproduced in other designs.

The introduction of the AR-15, designated the M16A1, in the Vietnam War was not auspicious. The rifle rapidly acquired a reputation for jamming in the middle of combat with accounts of soldiers being found dead in the act of trying to disassemble and clean their rifles. For this reason and its plastic appearance, troops derided the rifle as the “Matty Mattel Toy.” It came off as distinctly inferior in encounters with the AK-47. The complaints finally triggered a Congressional investigation, which found that the army has substituted a different gun powder than the one specified to save money and had also erroneously instructed the soldiers that the rifle did not need cleaning. Corrections were made and the rifle has remained in service ever since although it continues to require close maintenance to keep functioning. Kalashnikov and Stoner met in person, and when asked his assessment of the AR-15, Kalashnikov stated the rifle was “pretty good” although it had gone through more versions “than the hair on my head.” He had a large head of bushy white hair at the time. The rifle remains in service with the United States military in approximately its sixth version with the designation M-4.

Wound Ballistics

Guns do their work through the bullet that strikes the target, so it is appropriate to examine their effects, especially on human targets that military weapons are designed for. During the retreat of the German Army in The Forgotten Soldier , Sajer describes an encounter between his unit and Russian villagers who are emboldened by the Germans’ imminent defeat. As the villagers begin shouting insults and hurling rocks at the heavily armed soldiers, Sajer watches as the hands of a comrade holding a machine gun begin shaking with anger and self-restraint. The soldier calls out, “Watch it, you pigs, or we’ll drill you full of holes.” This is an accurate description of the effect of a bullet.

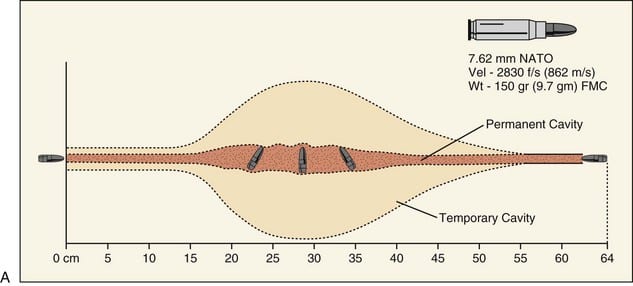

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Upon striking a human body, a bullet disintegrates everything in its path, leaving a tunnel behind it. Where the bullet destroys vital systems, such as organs, arteries, and major veins, death is instantaneous. The wound channel also allows for extravasation, the loss of blood from the body, that can lead to death as well. But the bullet does even more.

There is too much kinetic energy contained in a bullet for it to be released only forward, and it also exits sideways. The destruction caused here reveals that the bullet itself is not the only or even primary agent of destruction in a gunshot. It is more of a trigger that initiates another physical process to cause damage. This other physical process is based on the fact that the vast majority of the human body, other than a few pounds of chemicals, consists of water, and it is this seemingly-innocuous and universal substance that is the agent of damage. The relevant feature of water is that it is incompressible. This seems unintuitive with our daily experience of water flowing over and around us. Yet it can be seen in the everyday act of holding water cupped in both hands, and then squeezing your hands together to make the water squirt out. The supersoaker water gun operates by the same principle. Water does not absorb pressure but moves in response. When enclosed in a container, water transmits pressure instantaneously to all parts of the container.

The human body can be modeled as a series of enclosed containers of water down to the microscopic level of the cell, the subunit of the body, which is essentially a small bag of water. Once the pressure exceeds a certain limit, the container ruptures like a water balloon. This is the effect of energy released laterally from a bullet traveling through the body. Like a balloon, containers of water in the human body expand in a process of cavitation which is subdivided into two types: permanent and temporary cavitation. When the elastic limit of the membrane is exceeded, it ruptures in permanent cavitation; just like a rubber band that has been snapped, the membrane cannot reform. Minus the energy required to do this, the energy wave continues onward. After a point, the energy drops below the elastic limit, and the tissue structures can rebound like a rubber band in temporary cavitation. But even here, there are gradations. Just as a rubber band, after repeated stretching, loses elasticity, so do tissues that have been stretched up to a certain point. The wave of hydrostatic pressure, moving radially outward from the bullet’s path, is responsible for much of the damage of gunshots to human bodies.

The caliber innovation of the AR-15 rifle introduced a variation on this process. Stoner’s main reason for increasing the bullet velocity in the 5.56X45mm caliber was to cause additional damage. The stability of rifle bullets, which permitted long-range accuracy during the Civil War, depends on a close relationship between bullet weight, velocity, and rotation (induced by rifling). Disturb any factor, and the bullet becomes unstable. Stoner changed all these variables by reducing the bullet weight, increasing velocity, and reducing the rotation rate. When these bullets struck a body, they behaved erratically. This began with a tumbling effect wherein the bullet began cartwheeling through tissue, creating a much wider and more ragged channel with its long axis, rather than its diameter. In addition to instability in orientation, the 5.56mm bullets were also unstable in direction. When encountering bone or different tissue density, the bullets would carom off, making a new path of destruction. Rather than a straight tunnel, the 5.56mm bullets would tear a zigzag channel with more lateral cavitation than other calibers. This explains the comments of some doctors that wounds from these rounds “look like a bomb had gone off in there.” And they also explain how even when wounds are sewn up, they sometimes collapse. This indicates semi-permanent cavitation where, even though a structure has survived, it has suffered such deep fibrous tearing that it can no longer support itself. There is a general medical opinion that wounds to the thorax with this caliber are typically fatal.

Does this mean that the 5.56X45mm caliber is more lethal than the 7.62X39mm caliber of the AK-47? Not necessarily. As with other of Stoner’s innovations, his choice of caliber had unforeseen drawbacks. While bullet instability could produce larger wounds, it would not always. Sometimes, the bullet would deflect out of the body in a harmless direction. It is also easily deflected by obstacles such as panes of glass or tree leaves, or simply stopped by barriers that would not deter heavier calibers. Other times, the bullet’s energy would be used up in a meandering pathway and remain in the body without causing the deadly extravasation. The slow bullet rotation of the original caliber also degraded accuracy, making it harder to hit the target. However, increasing the rotation decreased the bullet’s destructiveness, and the small bullets would sometimes punch straight through a body without causing serious damage. Finally, where the small bullets take advantage of kinetic energy by tearing body structures, they are disadvantaged by the properties of momentum. Momentum defined as (mass X velocity), requires sufficient mass to knock down a target, just as a billiard ball requires a sufficient mass to move another billiard ball. Unlike John Browning’s heavy .45 ACP bullets, the 5.56mm bullets do not knock down targets, which has a special value in a combat environment. The injured target must then coordinate its limbs while in shock and work against gravity to stand up, making the soldier less of a threat.

In contrast, the heavier .30 caliber bullets of the AK-47 can knock the assailant down, and the gun platform can deliver these bullets much faster than a full-power rifle. Thus, there are two kinds of “assault rifle ammunition” with different effects. While the smaller 5.56X45mm ammunition has more of a mutilating, shredding effect than the 7.62X39mm, neither is ultimately more dangerous than the other.

What is an assault rifle?

The history of firearms can shed light on one of the foremost issues of gun violence. This discussion is driven by the unprecedented number of mass shootings which are often carried out with a version of the AR-15 rifle. As a way to eliminate this crime, it has been proposed to ban Ar-15s as part of the category of assault rifles, similar to the way that machine guns were regulated after the gangster-era as “unusual and dangerous weapons.” However, the proposed regulation begs the question of what exactly is an assault rifle. The weapons used in the shootings are civilian versions of the M-16 series of rifle, virtually identical except for the selector switch for fully automatic fire.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en The two sides of gun control and gun rights have a deep interest in this definition. Defining AR-15 rifles as assault weapons is a prerequisite towards regulating them as desired by the gun control faction and resisted by the gun rights movement. As found with other topics of cultural discourse, everything hinges on the definition used, and each side has found a definition to suit its purpose. We will briefly review the two sides and the arguments for and against found in the popular conversation. Supporters of gun rights cite the U.S. Army for a definition that an assault rifle has a selective fire capability, including a setting for fully automatic fire. Since civilian AR-15 do not have this capability, they do not meet the definition and should not be regulated. However, neither the National Rifle Association (NRA) or anyone else has referenced a specific document published by the U.S. Army with this definition. On the other hand, proponents of gun control define an assault rifle with the definition used by the Assault Weapons Ban (AWB). This definition was based on six “evil features” (a gun rights term).

- Flash hider

- Attachment point for a bayonet

- Rails for a grenade launcher

- Large, detachable magazine

- Pistol grip

- Folding stock

An assault rifle is defined as any rifle having a large, detachable magazine (item 4) and any other two on the list; this would include civilian AR-15 rifles. Gun rights supporters argue that this definition is flawed in only considering the outward, “cosmetic” appearance of the weapon and not the action that is more essential. Since the semiautomatic action of the civilian AR-15s is identical to many other weapons not considered for banning (such as the M1 Garand), the definition is considered misguided and unfair to owners of these weapons. These are the major points of debate on banning assault rifles, which is currently deadlocked. Both definitions can be understood as theories or abstractions about their subject, so a possible new line of inquiry could consider the counterpart of theory: reality or history. Doing so can make two contributions to the discussion. The first is in response to another point advanced by gun rights supporters that the term “assault rifle” is not even a specialized military term but a completely arbitrary designation. Any gun, weapon, or even implement, such as an automobile, used for violence, can be labeled an “assault weapon” according to this argument. However, history shows that the term “assault rifle” is not arbitrary at all. It was a historical term, referring to a distinctive type of weapon which had an important, measurable impact on history and on the subsequent design of weapons. To deny the existence of such a weapon flies in the face of facts and makes history less, rather than more, comprehensible. The historical record suggests that there is value in recognizing a type of weapon called an “assault rifle” based on the features of the original weapon of that name, the Stg. 44. Secondly, history makes clear that the assault rifle was not an entirely original creation such as Browning’s gas design, inspired by grass in the wind. Rather, the assault rifle combines technologies developed over a long period of time including carbines (shortened rifles), detachable magazines, gas-operated semi-automatic weapons, machine guns, and pistol grips. This composite history suggests that there is no exact line distinguishing an assault rifle from other guns but rather a series of degrees. In determining the degree of difference, one would focus, naturally, on the automatic feature which is the only one separating the civilian AR-15 rifle from the military version. One can do this by examining the automatic feature in the doctrine of the Stg. 44 and the U.S. Army today, but an exact determination here as well as the legal implications remain to be discussed.

Bibliography

Constitutional History

- Cottrol, R. J. (1994). Gun Control and the Constitution: Sources and Explorations on the Second Amendment. New York: Garland Publishers. Shields Library General Collection A7 G86 1994

- Cramer, C. E. (1999). Concealed Weapon Laws of the Early Republic: Duelling, Southern Violence, Moral Reform. Westport: Praeger. Shields Library General Collection KF3941 .C729 1999

- Cornell, S. (2006). A Well-Regulated Militia: The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York: Oxford University Press. Shields Library General Collection KF4558 2nd .C67 2006

- Cornell, S., & Shallhope, R. E. (2000). Whose Right to Bear Arms Did the Second Amendment Protect? Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. Shields Library General Collection KF4558 2nd .W567 2000

- Defensor, C. (1970). Gun Registration Now–Confiscation Later? New York: Vantage Press. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .D44

- Freedman, W. (1989). The Privilege to Keep and Bear Arms: The Second Amendment and Its Interpretation. New York: Quorum Books. Shields Library General Collection KF3941 .F74 1989

- Gottlieb, A. M. (1981). The Rights of Gun Owners. Aurora: Caroline House Publishers. Shields Library General Collection KF3941 .G674

- Kates, D. B. (1979). Restricting Handguns: The Liberal Skeptics Speak Out. Croton-on-Hudson: North River Press. Shields Library General Collection A75 R47

- Winkler, A. (2011). Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Shields Library General Collection KF3941 .W56 2011

- Uviller, H. R., & Merkel, W. G. (2002). The Militia and the Right to Arms, or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Shields Library General Collection UA42 .U95 2002

Military History

- Bull, S., & Rottman, G. (2008). Infantry Tactics of the Second World War. New York: Oxford. Shields Library General Collection UD157 .B85 2008

- Bull, S. (2010). Trench: A History of Warfare on the Western Front. Oxford: Osprey Publications. Shields Library General Collection D530 .B848 2010

- Carman, W. Y. (1955). A History of Firearms From Earliest Times to 1914. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Chickering, R., & Forster, S. (2000). Great War, Total War: Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, 1914-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shields Library General Collection D530 .G68 2000

- Coates, E. J., & Dean, T. S. (1990). An Introduction to Civil War Small Arms. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications.

- Cramer, C. E. (2006). Armed America: The Remarkable Story of How and Why Guns Became as American as Apple Pie. Nashville, TN: Nelson Current. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .C73 2006

- Hogg, I. V., & Weeks, J. S. (1985). Military Small Arms of the 20th Century: A Comprehensive Illustrated Encyclopedia of the World’s Small-Calibre Firearms. London: Arms & Armour Press. Shields Library General Collection UD380 .H58 1985b

- Horwitz, J., & Anderson, C. (2009). Guns, Democracy, and the Insurrectionist Idea. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Shields Library General Collection U5 H626 2009

- Jones, K. R., Macolo, G., & Welch, D. (2013). A Cultural History of Firearms in the Age of Empire. Burlington: Ashgate. Shields Library General Collection G7 C85 2013

- King, A. (2013). The Combat Soldier: Infantry Tactics and Cohesion in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shields Library General Collection UD157 .K56 2013

- Sajer, G. (1971). The Forgotten Soldier. New York: Harper & Row. Shields Library General Collection D764 .S234513

- Samuels, M. (1992). Doctrine and Dogma: German and British Infantry Tactics in the First World War. New York: Greenwood Press. Shields Library General Collection 3 .S26 1992

- Senich, P. R. (1987). The German Assault Rifle: 1935-1945. Boulder: Paladin Press. Shields Library General Collection G4 S46 1987

- Silverman, D. (2016). Thundersticks: Firearms and the Violent Transformation of Native America. Cambridge: Belknap Press. Shields Library General Collection W2 S55 2016

Gun Violence/Crime

- DeConde, A. (2001). Gun Violence in America: The Struggle for Control. Boston: Northeastern University Press. Shields Library General Collection HV7436 .D43 2001

- Giffords, G. D., & Kelly, M. E. (2014). Enough: Our Fight to Keep America Safe From Gun Violence. New York: Scribner. Shields Library General Collection HV7436 .G54 2014

- Kellner, D. (2008). Guys and Guns Amok: Domestic Terrorism and School Shootings from the Oklahoma City Bombings to the Virginia Tech Massacre. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers. Shields Library General Collection U6 K45 2008

- National Research Council (U.S.) Committee to Improve Research Information and Data on Firearms, Wellford, C. F., Pepper, J., Petrie, C., & National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Law and Justice. (2004). Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. Shields Library General Collection HV6789 .N37 2004

- Schorr, K. (2017). Shot: 101 Survivors of Gun Violence in America. Brooklyn, NY: PowerHouse Books. Shields Library General Collection 3.U5 S56 2017

- Younge, G. (2016). Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives. New York: Nation Books. Shields Library General Collection HN90.V5Y675 2016

Hunting/Conservation

- American Rifleman Magazine. National Rifle Association. (1923). American Rifleman. Washington: National Rifle Association.

- Dray, P. (2018). The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America. New York: Basic Books. Shields Library General Collection SK41 .D73 2018

- Duda, M. D., Jones, M. F., & Criscione, A. (2010). Sportsman’s Voice: Hunting and Fishing in America. State College, PA: Venture Pub. Shields Library General Collection SK41 .D83 2010

- Grey, H., & McCluskey, R. (1955). Field & Stream Treasury: A Selection of Memorable Articles From America’s Number One Sportsman’s Magazine. New York: Holt. Shields Library General Collection SK33 .F45

- Herman, D. J. (2001). Hunting and the American Imagination Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press. Shields Library General Collection SK40 .H47 2001

- Roosevelt, T. (1893). The Wilderness Hunter: An Account of the Big Game of the United States and Its Chase with Horse, Hound, and Rifle. New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons. Shields Library General Collection SK45 .R6

- United States Department of the Interior. (1991). Enjoy Outdoors America: Hunting. (Shields Library Gov Info & Maps DOC I 1.2:H 92 ). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior. Shields Library Gov Info & Maps DOC I 1.2:H 92

Medicine

- Identifying Armed Respondents to Domestic Violence Restraining Orders and Recovering Their Firearms: Process Evaluation of an Initiative in California. Garen J. Wintemute, MD, MPH, Shannon Frattaroli, PhD, MPH, Barbara E. Claire, Katherine A. Vittes, PhD, MPH and Daniel W. Webster, ScD, MPH. American Journal of Public Health, published online ahead of print December 12, 2013;e1-e6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301484.

- Support for a Comprehensive Background Check Requirement and Expanded Denial Criteria for Firearm Transfers: Findings from the Firearms Licensee Survey. Garen J Wintemute. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. Published online 08 November 2013. DOI:10.1007/s11524-013-9842-7.

- Comprehensive Background Checks for Firearm Sales . Garen J Wintemute. In: Webster W, Vernick J (eds). Reducing Gun Violence in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. pp 95-107.

- Karlson, T. A., & Hargarten, S. W. (1997). Reducing Firearm Injury and Death: A Public Health Sourcebook on Guns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO807 K18r 1997

- Ladenheim, J. C., & Ladenheim, E. D. (1996). Firearms and Ballistics for Physician and Attorney. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Professional Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO807 L34 1996

- Owen-Smith, M. S. (1981). High Velocity Missile Wounds. London: E. Arnold. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO807 O94 1981

- Removing Guns from Batterers: Findings from a Pilot Survey of Domestic Violence Restraining Order Recipients in California. Katherine A Vittes, Daniel W Webster, Shannon Frattaroli, Barbara E Claire, Garen J Wintemute. Violence Against Women; 2013 19(5):602-616.

- Swan, K. G., & Swan, R. C. (1989). Gunshot Wounds: Pathophysiology and Management. Chicago: Yearbook Medical Publishers. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO807 S93 1989

- Hemenway, D. (2004). Private Guns, Public Health. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO 807 H498p 2004

- Tsokos, G. C., & Atkins, J. L. (2003). Combat Medicine: Basic and Clinical Research in Military, Trauma, and Emergency Medicine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection WO 800 C7294 2003

- Warlow, T. A. (2005). Firearms, The Law, and Forensic Ballistics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection W 700 W27 2005

- Zwerling, C., & McMillan, D. (1993). Firearms Injuries: A Public Health Approach. New York: Oxford University Press. Carlson Health Sci Library General Collection W1 AM592 v.9 no.3 suppl.

Sociology

- Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color-blindness. New York: The New Press. Shields Library General Collection HV9950 .A437 2010

- Bakal, C. (1966). The Right to Bear Arms. New York: McGraw-Hill. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .B3

- Barlow, H. D. (2000). Criminal Justice in America. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Shields Library General Collection HV9950 .B36 2000

- Braman, D. (2007). Doing Time on the Outside: Incarceration and Family Life in Urban America. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Shields Library General Collection HV9950 .B7 2004

- Baum, D. (2013). Gun Guys: A Road Trip. New York: Knopf. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .B38 2013

- Canada, G. (1995). Fist, Stick, Knife, Gun: A Personal History of Violence in America. Boston: Beacon Press. Shields Library General Collection V55 C36 1995

- Carlson, J. (2015). Citizen-Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .C37 2015

- Farr, V., Myrttinen, H., & Schnabel, A. (2009). Sexed Pistols: The Gendered Impact of Small Arms and Light Weapons. Tokyo: United Nations University Press. Shields Library General Collection HV7435 .S49 2009

- Harrington, M. (2012). The Other America: Poverty in the United States. New York: Scribner. Shields Library General Collection HV91 .H3

- Kukla, R. J. (1973). Gun Control. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .K79

- Kohn, A. A. (2004). Shooters: Myths and Realities of America’s Gun Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shields Library General Collection HV8059 .K65 2004

- Lepore, J. (2010). The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle over American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Shields Library General Collection 9 .L46 2010

- Prothrow-Stith, D., & Weissman, M. (1993). Deadly Consequences: How Violence Is Destroying Our Teenage Population and a Plan to Begin Solving the Problem. New York: HarperPerennial. Shields Library General Collection 4.Y68 P76 1991