The Ray Hunold Photograph Collection Storytellers and Nature Photography

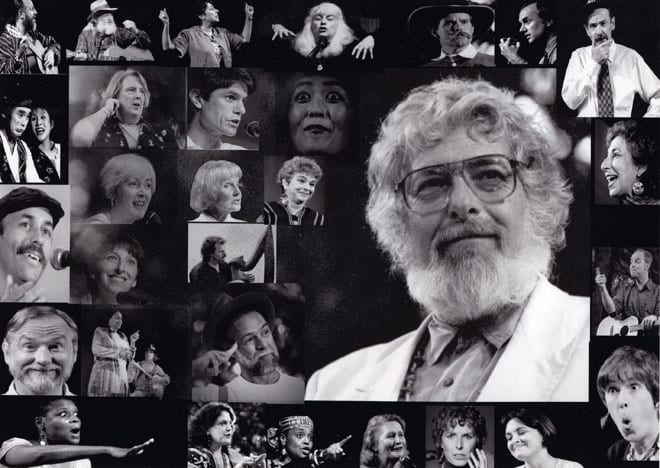

Featured image: Ray Hunold, Freelance Photographer (1933-2010)

“A camera is just part of me.”

Ray Hunold

Biography

Ray Hunold was born in 1933 in Brooklyn, New York. He began school in Brooklyn, New York, but moved to Queens at the age of seven. He then attended PS-99 and went on to Forest Hills High School. After high school, Hunold attended the School of Modern Photography in New York. Hunold was drafted into the Army. He attended the U.S. Signal Corp School of Photography at Monmouth, New Jersey. During the service he spent some time at the Presidio in San Francisco. One assignment involved photographing a general as he met with the San Francisco mayor, attended parades or other publicity shots. The rest of the time Hunold was free to roam around the city taking photographs of his own interest, such as views of the Mission Delores graveyard. It was during this assignment that Hunold gained his first appreciation for San Francisco. A car accident kept Hunold from being assigned to the photo unit that was being sent to White Sands, New Mexico where they were testing atomic weaponry.

Hunold served until 1959 receiving an honorable discharge. He now discovered his love of nature and travel photography. The Audubon Society became his agent, which was later taken over by Photo Researchers. Through a meeting with the editor of the New York Times Sunday Travel Section, Hunold started doing picture layouts for the Times on a regular basis.

Hunold returned to New York, where he met his wife Bernice Frankel at a mystery writers club in the early 1960s. Bernice was a children’s book editor and author. She worked for Macmillan Company on Harris-Clark readers, writing original stories as well as selecting and adapting material as texts for lower grades. She was the children’s book editor for Abelard-Schuman Ltd. and then for Parents’ Magazine Press. She was a weekly columnist for “Books for Children” in the Saturday Review Newspaper Syndicate during the 1950s. Bernice wrote nine children’s books including Half-as-Big and the Tiger (1961), Tag-along (1962), Grandpa’s Policeman Friends (1967) and two works of literary criticism such as Pride and Prejudice: notes and criticism (1965).

The couple married in 1966. The family consisted of Bernice, Ray, and their German shepherd dog, Homer. As Hunold had enjoyed his time in San Francisco during his military service, they decided to move west to San Francisco in 1970.

The Hunolds were to find many common interests. It was to be Bernice Hunold’s love of storytelling that was to draw Ray Hunold into the storytellers’ world as a photographer. Over the years Bernice Hunold took classes on storytelling. She continued to write for Town and Country, American Home, and other publications. A love of travel and adventure set them on the road to many parks throughout the U.S.

Ray Hunold passed away on May 28, 2010. It was his wish that his photograph collection be available to researchers and so UC Davis is pleased to maintain Ray Hunold’s magnificent legacy to be found in his beautiful portraiture and landscape images.

First Photograph

If you go far enough back in my childhood I recall my mother taking me for a walk after we attended church in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York. I was about seven. My mother took some pictures of me with an old Kodak folding camera (which I still have) and I asked to take a picture of her. I did and after the film was developed and printed, I really thought it was some sort of magic.

Clarence Wesley Gibbs, A Mentor

Ray Hunold was about fifteen years old, when he met photographer Clarence Wesley Gibbs who lived in his same apartment building. Ray spent most of his evenings talking and working with Mr. Gibbs and his wife about photography. Mr. Gibbs had written articles or had his photographs appear in many photographic magazines of the time and several books. He had worked with Edward Steichen in Washington, DC, during World War II. He knew Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz. Gibbs was a ranked salon exhibitor. Hunold states,

I sat across from this man every night for many years, just listening to his stories and learning, or at the very least, trying to learn how this magic worked.

At 17 First Photograph Contest Award

When Hunold was seventeen years old The New York World Telegram and Sun held a photograph contest. Hunold submitted three photographs, one was a scene of a recent fire in an old building, and that was the one that took third place in the newspaper contest. The prize was a check for $40, which Hunold spent in the Peerless Camera store in New York City.

I had made the amazing discovery that I could earn money with my camera!”

Photographer/Author

By the time Hunold was in his early twenties, his photographs had been published in several magazines. During his beginning career in New York City as a freelance photographer, Hunold worked for a number of customers from commercial accounts to the Republican National Committee to “Elect Ike as President.” Early in his career nature photography was a specialty.

Nature and Landscape Photography

The Hunold Collection consists of over 70,000 color transparencies that cover most of the southwestern United States, Mexico, Baja and Alaska and over 50,000 black & white negatives many from the East coast including pictures from the New Jersey shoreline up to Gaspe, Canada.

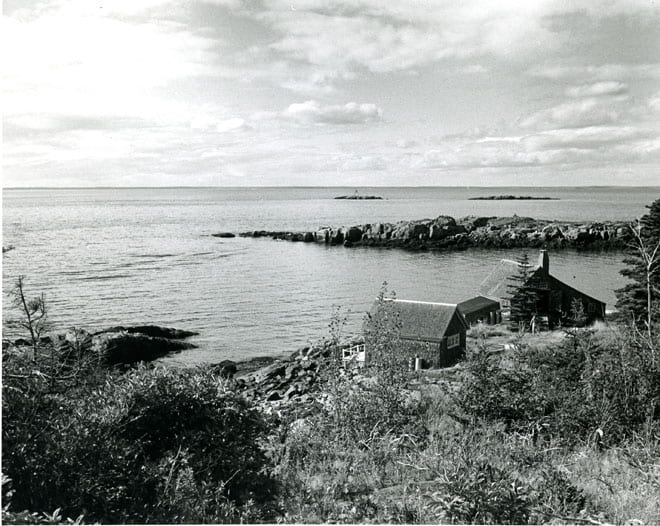

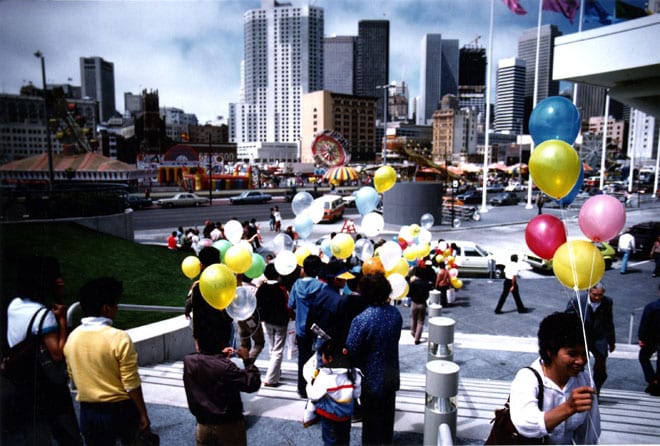

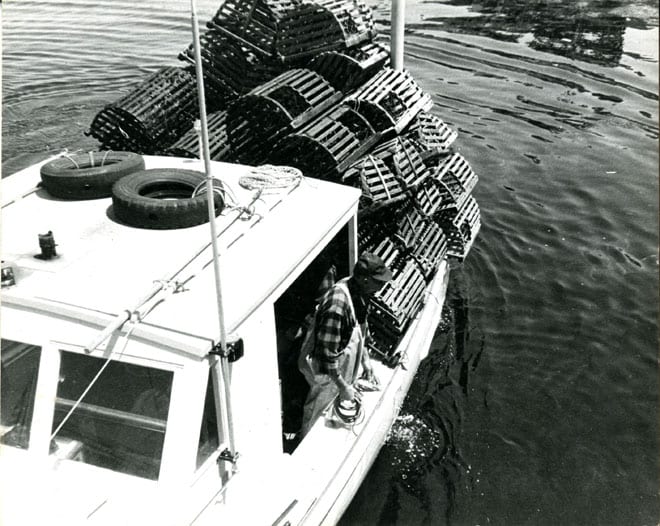

The Hunolds traveled to almost every national park, national monument and state park ranging from the Great Swamp in New Jersey to Prairie Creek and The Redwood National Park in Northern California. Hunold also photographed extensively on the island of Monhegan off the coast of Maine. The Hunolds traveled from Alaska to Mexico down the Yucatan with Hunold photographing along the way and at every site. The western photographic subjects range from Boojum Trees in Baja to known Native American ruin sites to be found in the southwestern deserts of the United States. Hunold photographed deserts, seacoasts, woodlands, the rain forest in Olympia, rock country such as the Grand Canyon and Big Bend in Texas, as well as many street scenes in San Francisco. Wildlife and plants, especially flowers are often chosen subjects. As a travel photographer, people were also included in many of the images.

The Hunolds toured Europe in 1985 and the United Kingdom and New Zealand in 1986. Hunold jokingly stated that this was something he did for his wife to pay her back for all those Indian sites he had dragged her to see.

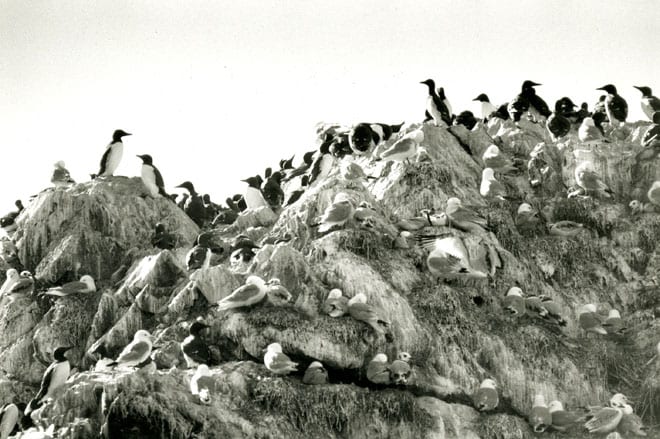

He stated, I loved Alaska. The first time I saw it was when we drove the Old Alcan highway up to Alaska. I will never understand the words that Robert Service is said to have uttered about Alaska being a place for old men, because if you were young you would spend your life comparing everyplace else to Alaska. Our second and maybe our last trip was when we flew in for two weeks in 1996.

Monhegan Island, Maine.

San Francisco Fair, 1983.

Maiden Lane, San Francisco, 1983.

Lobster boat, Monhegan Island, Maine.

Gull Rock, Homer Alaska, 1996.

Embarcadero Center, San Francisco, 1983.

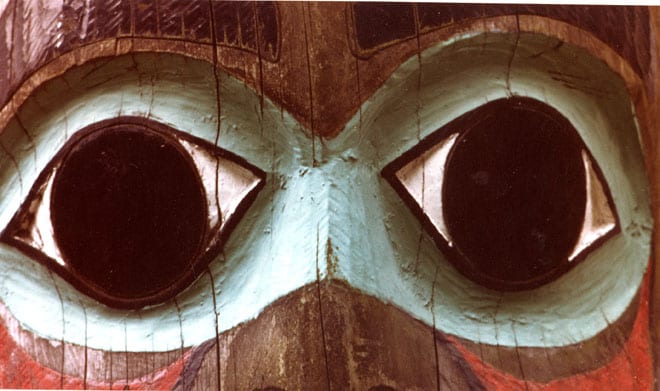

Totem pole, Sitka, Alaska, 1979.

Sea kayaking near Northwestern Glacier, Alaska, 1996.

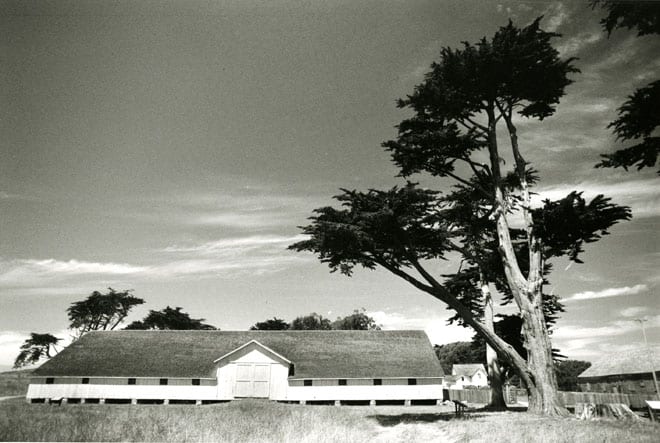

Pierce Ranch, Point Reyes National Seashore, 1993.

Death Valley, California, 1983.

Otago Peninsula, New Zealand, 1986.

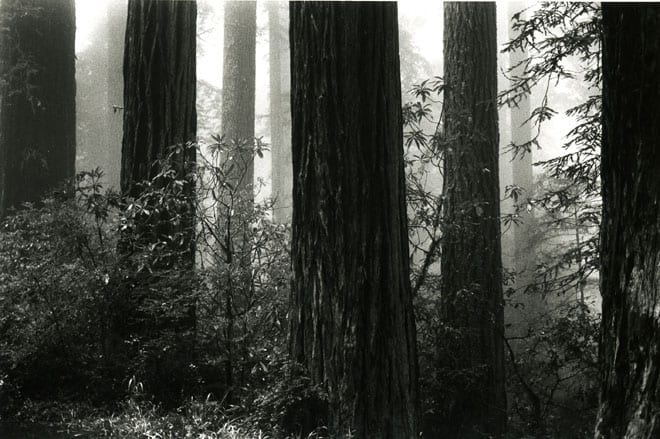

Lady Bird Johnson Grove, Redwood National Park, 1993.

Golden Mantle ground squirrel, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, 1996.

Canada goose, Buttertubs Marsh Wildlife, Refuge, Vancouver Island, Canada, 1990.

New Zealand, 1986.

Ray Hunold Photograph Collection of Storytellers

Photographer for the Sierra Storytelling Festival

Ray Hunold accompanied his wife, Bernice, to the Sierra Storytelling Festival in Nevada City, California in 1988. It was natural for him to pull out his camera and he began to catch the storytellers in their act. The Hunolds met Steve Sanfield, the founder and director, of the Sierra Storytelling Festival. When a hired photographer did not show up at the Sierra Storytelling Festival, Ray Hunold was asked to step in and shoot photographs for the Festival’s files. Hunold then became the official photographer for the Sierra Storytelling Festival from 1988 through 2002. By 1990, Hunold started going to most of the other major festivals in California and he became the official photographer for many of these events. He also attended the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee several times.

Hunold did, however, offer his work to the storytellers themselves; many became his clients. His photographs were used for their publicity on book covers and audiotapes. Ray Hunold became the photographer for some of the best storytellers from both the West and East coasts of the United States.

Photographing storytellers was a labor of love, as there was little money to be made. Hunold loved to photograph people in action and enjoyed both the performances and working in the creative world of storytelling.

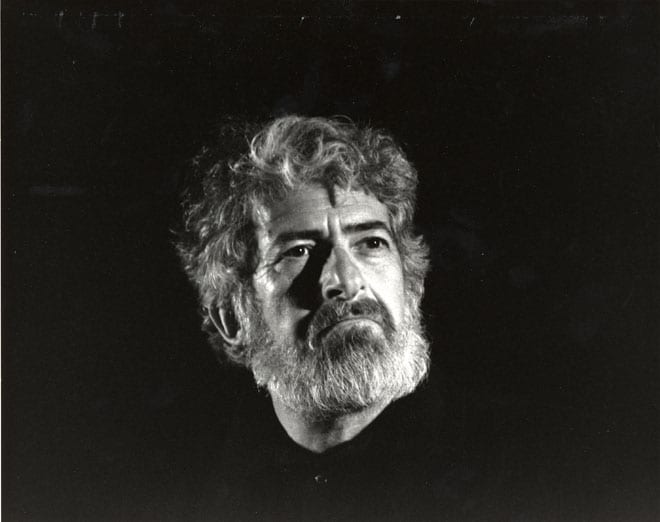

Steve Sanfield

Founder and director of the Sierra Storytelling Festival held in Nevada City, California. Sanfield had a “hands on” approach to the festival that greatly impressed Ray Hunold. An author and phenomenal storyteller, Sanfield founded the Sierra Storytelling Festival in 1985 and served as its director until his retirement in 2002.

Storytelling Events

The Hunolds attended many storytelling festivals throughout California and the nation and Hunold was the selected photographer for many other festivals. The Hunolds attended the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee, the Mariposa Storytelling Festival, the San Juan Capistrano Storytelling Festival, the Forest Festival in Port Angeles, Washington and the Timpanogos Storytelling Festival in Orem, Utah.

Working with Storytellers

Hunold stated, “I spoke to the storyteller before the shoot and explained who I was, what we [the festival staff] wanted to do with the pictures and if they asked, as most of the tellers did, supplied finished proofs for them to look over. I always tried to send them proofs to be looked over. My accountant always said that my fee for the storyteller was too low and that while he understood that most did not make much money, he did not feel I should support them all.

”

Photographing storytellers was a labor of love, as there was little money to be made. Hunold loved to photograph people in action and enjoyed both the performances and working in the creative world of storytelling.

The one question I can remember asking most, if not all the storytellers was – “Was there any pose or facial expression that they did not want me to photograph?” Only one teller asked me not to photograph him when he told a certain story. I did not and everything else worked out fine. One storyteller that I had photographed at many other festivals suddenly asked me to stop because he told me he could hear every click of the camera, as I was shooting. This happened in Port Angeles, Washington at the Forest Festival, and I felt it was more or less the way the sound bounced off the low ceiling.

Hunold had great admiration for the storytellers and the evident joy they put into their work “The storyteller puts endless hours into repeating the same story, until it has really become a part of the storyteller. Every storyteller knows that how the story will go over depends not only on how well he tells the story, but also that he has really brought the story to the audience and they are hanging on what the next word will be. When the audience is waiting breathlessly, it makes for a great performance.

”

At many festivals each storyteller works on stage for a set period of time. It may be just fifteen minutes, sometimes thirty minutes. How the teller wants to use the time is usually up to him or her.

One thing Hunold noticed was that the better storytellers were more flexible with their time. They knew when to end a story quickly that was not going well and stretch out a story, if it was going well.

It is really different with each place you photograph. The Sierra Festival was a rare place where they had a soundman and also someone that could handle the lighting. Every photographer should become friends with the people doing the lighting.

Ray Hunold typically ended up shooting between 20 to 25 rolls of film during the three-day Sierra Storytelling Festival.

Children

Children are a wonderful audience, because they quickly lose interest and show that very clearly. You can see in my photographs of the children’s concerts, if the kids are really paying attention. And you can see the trust on their faces. They know that at the end of the story, the hero will always win. After all, try to remember a telling when the hero loses.

Action Images versus Posed Studio Portraits

Ray Hunold preferred to photograph the storytellers with a spotlight on them on stage. “For the most part, they will forget about me and as professionals will become immersed in their story.

” Hunold recalls, “At night at the Sierra Festival they will only hear the click of the camera from time to time. Once a storyteller asked why she had heard me click once or twice during her fifteen minutes on stage. She was worried that the others and I listening were not enjoying the story. She made the simple statement that the click of my camera was the only way she really knew there was anybody out past the footlights. I took it as a very nice comment, since I do not use flash or anything, but just the stage lights. The only other people that may hear the click are the few that sit near me.

”

“Storytellers often repeat an aspect of the story three times. For instance, the maiden goes to the ball three times or the hero has three wishes. By watching carefully, you get to know the facial expressions of the storyteller. I pick an expression I like and catch it the next time around.

”

Information was obtained through an interview with Ray Hunold and Bernice Hunold by Daryl Morrison, September 27, 2004.

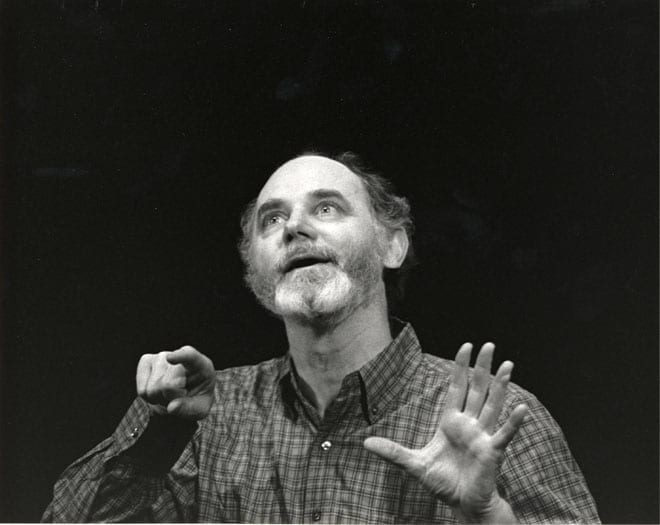

Gay Ducey, Sierra Storytelling Festival, July 1988.

Diana Ferlatte, Sierra Storytelling Festival, July 1989

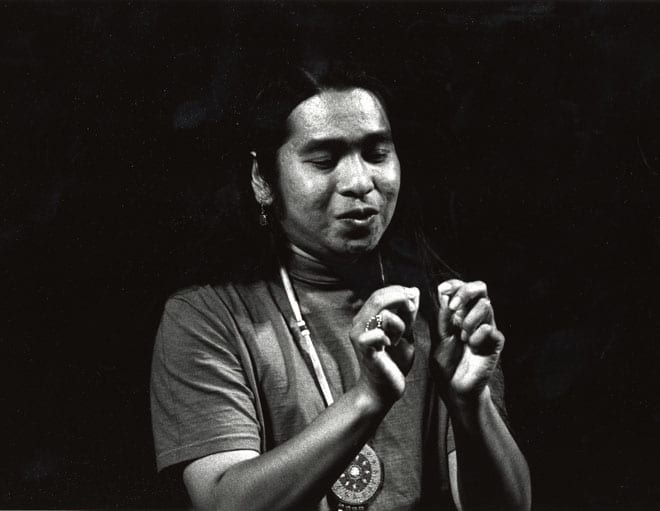

Johnny Moses, Sierra Storytelling Festival, July 1991

Olga Loya, Los Angeles Basin Storytelling Festival, October 1988.

Ruth Stotter, Mariposa Storytelling Festival, March 1989.

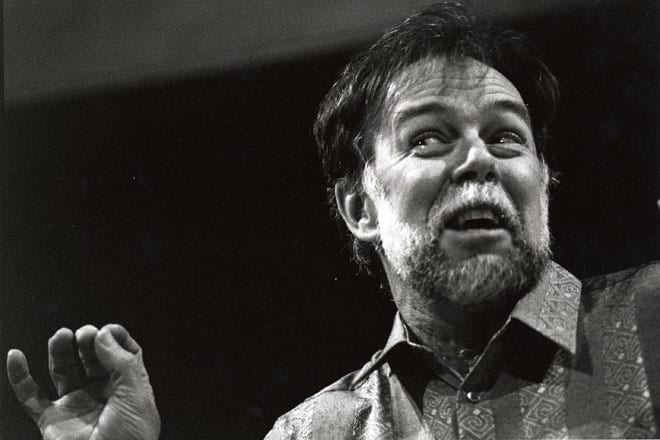

Jackie Torrence, National Storytelling Festival, Jonesboro, Tennessee, October 1992.

Bob Jenkins, TELLABRATION, November 1991.

Susan Strauss, Mariposa Storytelling Festival, March 1992.

Jay O’Callahan, Los Angeles Storytelling Festival, 1989.

Brenda Wong Aoki, TALES, March 1989

Donation and Use Information

The Ray Hunold Collection Donated to Special Collections

As Ray Hunold neared the celebration of his seventy-first birthday, he looked for an opportunity to preserve his work and make it accessible to researchers. Encouraged by friends, such as author/storyteller Steve Sanfield, Hunold gave the collection to Special Collections in the General Library, at the University of California, Davis in 2004.

Images (unless otherwise credited) are the property of the Regents of the University of California; no part may be reproduced or used without permission of the Department of Special Collections.