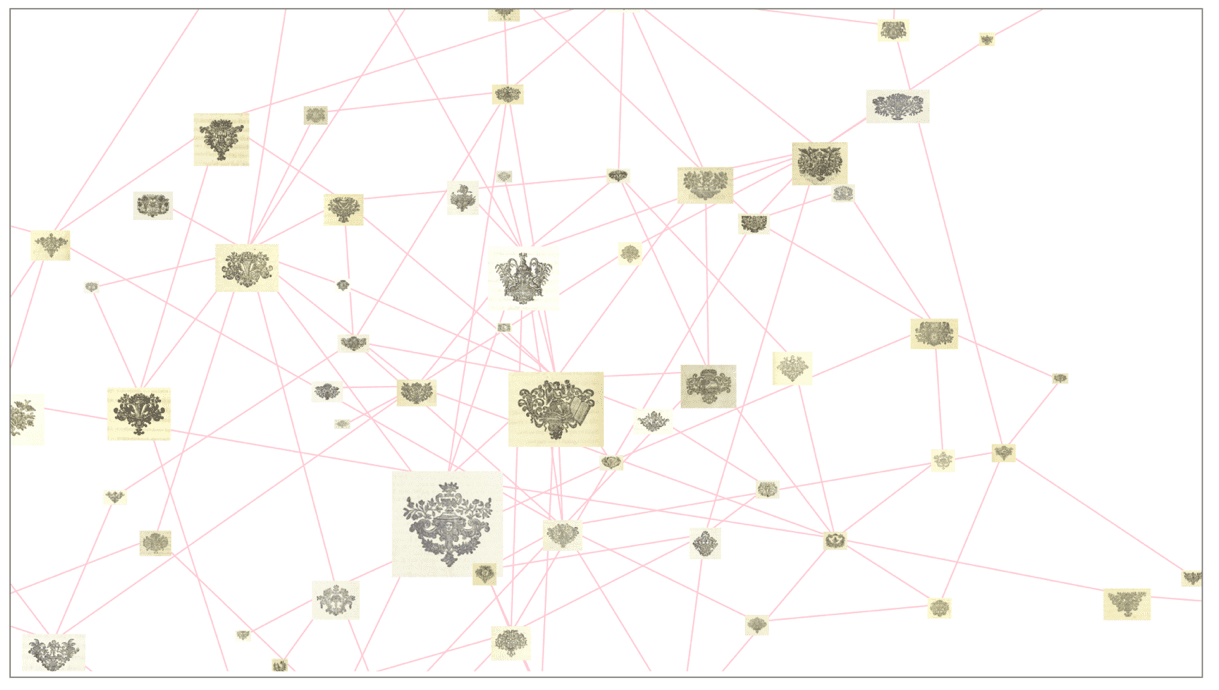

Keypoint matches of seed image and test image as identified and drawn by Archive Vision, or Arch-V, the software platform developed by Carl Stahmer and his team, which Getty’s grant will help them further enhance.

Getty Foundation Awards UC Davis DataLab $274,500 to Advance Groundbreaking Image Recognition Technology

The DataLab at the UC Davis Library, led by executive director Carl Stahmer, has been awarded a two-year, $274,500 grant by the Getty Foundation to tackle one of the thorniest problems in image recognition: building a tool to search for and identify images that are similar — though not identical — to one another. In this case, the tool would aid museums and libraries in cataloging early-modern prints by training an artificial intelligence on the existing catalogs of a coalition of libraries and museums from around the world.

Stahmer explains the technological challenge this way: “The distinction between ‘same’ and ‘similar’ is a known problem in image recognition. Sameness, although it took a long time to solve from a technical standpoint, is conceptually pretty straightforward: Is this a picture of the same thing? We know it’s the same because there are features that are identical and we’re matching on those features. For example, if you have a drawing of someone and there were multiple copies printed, we can find those copies: that’s the sameness problem, and we have that nailed. Our software can even handle if, say, half of the image was ripped away, or there was improper inking of one of the prints.”

“Similarity is a different problem,” he continues, “because similarity lives in your head.”

The ability to identify two images as similar depends on connections or associations we make based on cultural context — not just the features of the image, but its meaning.

“For example,” Stahmer says, “take one picture of a man on horseback, wearing a headdress with an army behind him; another image of two people sitting on chairs with people bowing in front of them; and a third image of a person’s face wearing a crown. As a human, I’d say, ‘These are all about royalty.’ But visually, there is no sameness at all: they look nothing alike.”

The Getty grant will allow Stahmer’s team to work on technological approaches to the similarity problem. And, Stahmer says, “That is, so far, an unsolved problem.”

“A game-changer for museums and print scholars”

The “similarity” problem has many applications. Search engines like Google are working to identify individual behavioral patterns so they can provide search results that you will find relevant. Libraries and museums have a different problem: they need to be able to describe the cultural artifacts in their collections in a way that is rooted in community consensus — a shared understanding of what constitutes similarity.

Heather MacDonald, senior program officer at the Getty Foundation, who heads up its Digital Art History initiative, describes the challenge: “Since at least the 18th century, museums have collected prints in large numbers; some museums own thousands or even hundreds of thousands of prints. The sheer scale of these collections has made cataloging those prints and sharing information about them extremely difficult.”

But if cultural institutions could find similar images in other collections, cataloging information and metadata entered by one institution could be quickly and easily used by others — saving time, reducing repeat efforts, and increasing consistency of how similar works of art are described by different institutions.

Stahmer proposes to solve this problem by building a global network of museums and libraries, all connected via a common software platform his team created called Arch-V, or Archive Vision. Museum or library staff would upload a scan or photo of a print they need to describe for their catalog (even a photo taken with a smartphone would work) and search for it in the system. If another institution in the network has a similar image, the software would display the cataloging record from that institution, which the person searching could then use as the basis for their own cataloging record.

What makes this approach different from what is possible with other tools is that the search is image-based, rather than depending on descriptions, or search terms, that might change from one institution to the next. If the Arch-V system comes up with a match, it’s because the images are similar.

“The digital technologies of image analysis — including projects like Arch-V that combine computer vision and machine learning — are becoming more and more powerful,” MacDonald says. “This idea has the potential to be a game-changer for both museums and print scholars.”

Solving the “similarity” problem through human-machine collaboration

Stahmer, who specializes in neural networks and machine learning — in other words, teaching computers to recognize patterns so they begin to “think like us” — sees museum and library catalogs as a key to improving image search.

Because human beings, with their innate ability to evaluate and apply cultural context, have already cataloged large numbers of images in museum and library collections, that dataset of images and accompanying descriptions can be used to train a neural network to recognize and classify “similar” images — say, images of royalty, to return to the earlier example.

“Our ace in the hole is that, at least within the bounds of early printed materials, we have a nicely controlled body of scholarship that we can use to define what constitutes similarity,” Stahmer says. “You can bring that contextual information into it, and train the classification system on top of that groundwork.”

In this way, human-created descriptions help refine and enhance the search technology. That technology, in turn, helps people who are cataloging images find similar examples so they can do their work more efficiently. It’s a human-machine collaboration that improves as it goes.

The next phase of the work

Stahmer’s project is one of a number of grants in Getty’s Digital Art History initiative that provide support for art historians and related professionals to explore the opportunities afforded by new, digital technologies.

The grant will enable Stahmer and his team to pursue the next phase of development for Arch-V, which he began working on in 2012 with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, while he was still at UC Santa Barbara.

And the project is gaining momentum. A number of world-class museums and libraries have already expressed interest in participating. If their collections can be networked into a single, searchable pool, scholars will be able to use Arch-V to examine a whole host of research questions in new ways. As a research tool for historians — not just for libraries and museums themselves — Arch-V will be transformative.